#39KINO2019

TRADING ALONG THE RIVER

THE SOCIAL LIFE OF THE SARAWAK RIVER

FIRST, A GEOGRAPHY LESSON. RIVERS go through three stages in development – youthful, mature and old age – each stage showing differences in size, speed and behaviour. Of course, this sets up the obvious and slightly feeble joke: what makes a river just like a person? We both start out small, hurtling headlong down cliffs and rocks without care or caution, carving a way through the world, then settle into a more sedate pace worn by the passage of time, and finally we spread out for a leisurely and somewhat aimless meander, occasionally overflowing our banks, before we head out into the great, wide beyond.

But in reality, despite a tendency to anthropomorphize, rivers have had far more impact on us than we have on them. We might navigate them, dam them, clog them with plastic bags and other pollution and paddle in them, but mostly they just go on their way. That is the hope, anyway. For our part, as a species, we have gravitated to rivers wherever we can, clinging to their sides. Almost every major capital around the world has one, the names as famous as the cities themselves. Almost every settlement in Sarawak runs parallel to a river or stream, ideal for fight or flight, work and play, sustenance and celebration. The river runs through it all, bringing the outside world in, on its way downstream.

The Sarawak River is no exception. Of the 35 major rivers gazetted under the Sarawak Rivers Ordinance, the Rajang might be the longest, but Sungai Sarawak is the most defining. It has given its name to the basin, the country, the capital (briefly) and now the state. Unlike most rivers in the state which can trace their name back to some natural feature, the provenance of the name of Sungai Sarawak is unclear: the Malay word for antimony, perhaps, but alternate explanations compete for precedence. But one thing is for certain, the Sarawak River has been through its stages – a passage of time, people, movement and trade – bringing the world into Sarawak and Sarawak out to the world.

The much-mourned markets were easy access from the water, running along the river’s length.

The much-mourned markets were easy access from the water, running along the river’s length.

It is hard to know where to begin, perhaps in Kuching, at a mid-life stop on the maturing of the river and of Sarawak itself; perhaps at the Waterfront where the movement of the river is best expressed. Stand on the Kuching Waterfront today and a long line of water linking Sarawak’s people stretches out in each direction. Look upstream, up past the fork of Kiri and Kanan, the traditional stronghold of the Sarawak Malay at Lida Tanah, up past Bau, up past Padawan, to Sadir and Krokong, you will find the Bidayuh (broadly speaking, of course). Look downstream, down past Sejingkat, down past Bako, all the way to Muara Tebas, you will find the modern Malay (again, broadly speaking) and the Iban at Samarahan, who both still paddle upstream (well, under power these days) to ply the perahu tambang. Look around you, and you will see the arrival of a new world. The Chinese shophouses and temples, the Indian spice shops and mosques, the Brooke era buildings are testimony to the numerous people who all came up this body of water and, almost literally, set up shop.

Selling from a boat-shop and transporting goods was a way of trading

Selling from a boat-shop and transporting goods was a way of trading

Rows of wooden jetties, wharfs and godowns.

Rows of wooden jetties, wharfs and godowns.

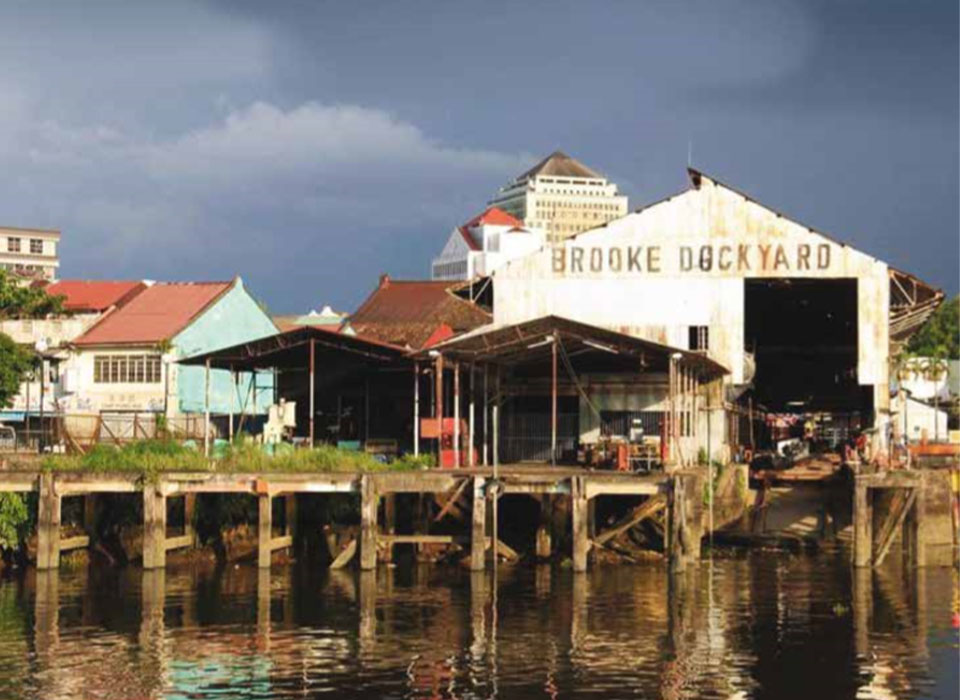

Stand on the Kuching Waterfront today and the ribbon of time coils around you, both in what remains and what has disappeared. Rewind a little and the neatly paved tiles of what is now a sedate heritage walk come loose to reveal the muddy flats of what was once the hurried heart of Kuching’s trading centre. Rows of wooden jetties, wharfs and godowns lined either side of its banks and boats thronged the centre of the stream. Kuching’s first petrol station once stood opposite the Tua Pek Kong, sited more in service of the far more abundant river traffic rather than what was then the occasional car. These boats evidenced transport but also trade and it was bustling.

The much-mourned markets were easy to access from the water, running along the river’s length. As John H.S. Ting describes in his ‘History of Architecture in Sarawak Before Malaysia’, these were “designed, procured, implemented and run by the government. A fish market had existed in Kuching since the 1860s, but new buildings were built in 1871 and 1885. A general market was built in 1883, next to the fish market.” They might have been government run, but they were people led. The river was the first pan-Sarawak highway and these markets were its busiest service station. Goods flowed here from the interior – rubber, pepper, cocoa, bird’s nests and rattan came down from the rocky upper reaches and salted fish, palm sugar, coconut and gambier from its open mouth. Everyone crowded round the Rumah Kupon to receive their license to trade, even climbing over each other to get to the front of the queue. These traders in turn had the chance to load their boats with salt, sugar, cooking oil and the uncertain delights of ready-made clothes, while they sampled the strange wonders of roti paun (bread), of all things.

This trade network worked both ways. While the kampung residents came down on occasion, the Chinese traders also went up, establishing outposts along the entire stretch. For those upstream, Kuching was a long way to come from Pangkalan Empat and Pangkalan Pan and an even longer journey back, so Batu Kitang, Siniawan and many small settlements in between became home to Chinese families, many of whom speak better Bidayuh than remote Mandarin, stocking a kedai runcit and serving as a jumping off point for further travels into the interior. Each became a minimarketplace, mimicking the main markets in Kuching where jungle goods were gathered before the long trip back down to the capital.

Lined either side of its banks and boats thronged the centre of the stream.

Lined either side of its banks and boats thronged the centre of the stream.

Of course, many of these outposts have stronger associations with underground resources than the landed plenty. Bau and Siniawan were the source of gold, Tegora near Krokong of mercury, and so the foundations of Sarawak’s modern economy began to emerge on this stretch of river. The product of Chinese labour in the mines, the workers sourced more from overland in Kalimantan than oversea in Singapore, made its way downstream and the final leg of the journey, from Sarawak to the world, was ensured, back on the same Kuching waterfront that oversaw local trade.

The Sarawak Steamship Company was established in 1875 to ‘solve the shipping problem in Sarawak.’ The Rajah wanted an income and export was the proposed source. Its warehouse still stands on the Waterfront but, at one time, its ships – the most famous named Rajamas and Pulau Kijang – plied the waters between Sarawak and Singapore, loaded with exotic treasures, underground and overground, in either direction. Close by were the offices of the Borneo Company, set up in 1856 to “take over and work Mines, Ores, Veins or Seams of all descriptions of Minerals in the Island of Borneo, and to barter or sell the produce of such workings”. One fed the other, taking trade out of the hands of the Chinese network and into the British Empire beyond, through the river mouth at Muara Tebas, of course.

Today, the Sarawak Steamship Company is a tour operator, its old godown now a handicraft centre. The offices of the Borneo Company are now the site of a high-class hotel. The first petrol station is now a highend café and the Waterfront itself is a gentrified promenade from which to take in the sights of the city. The tourist trade now trumps tradable goods and the main port has moved down to Pending and then Senari. The river has gone quiet, more for taxis and evening cruises than barter and exchange. But the human interchange has left its mark, an interconnectedness brokered by the river itself.

Karen Shepherd is the descendant of the second GM of the Borneo Company and also the final one, the facilitators of free trade in a new Sarawak. She has visited every section of the Sarawak River – young, mature and old – from Sadir, for a swim in a waterfall, to Muara Tebas, for a delicious seafood meal.